THE VILLA CHANTICLEER

Published in the Healdsburg Museum’s Russian River Recorder

Autumn 2008

By: Michael Haran

In 1942 the Rev. Mina Ross Brawner, M.D. of Melbourne, Australia jotted down notes of her early childhood in Healdsburg. “In 1896, I vividly remember the old but big Redwood tree on FitchMountain standing outside the fence surrounding my mother’s home. There was room for 20 picnickers in the hollow trunk. Its top was so high that it seemed, when viewed from our home-side, to pass the distant mountain and blend with the sky.”

One day I came home from school to find the big Redwood on fire. Its open throat was roaring like a furnace. Mother told us that the lighting had ripped down from the clouds and struck it. The roar was terrible. We could stand on the hillside and watch the fire relentlessly burn the heart of our old landmark.

But another rainstorm came down extinguishing the fire and the old tree was saved. Then suddenly a fearful crash and roar, the tree came down. We rushed to the spot – mother and the three children who were home. Was the tree gone? The nook seemed filled with the fallen trunk and branches. Quickly I returned to our cottage and secured a tape-measure. Together we measured the top of the huge tree lying like a giant submarine on the ground. It was 90 feet long. Looking up to my surprise the tree seemed to be as tall as before.

In 1943 Rev. Brawner returned to Healdsburg to see if the old Redwood still stands. It was and she wrote “Old Stovepipe they call you now, and wonder how it happened. But you and I remember. You have kept your secret all these years, but tonight I am telling the world you battled against all obstacles – and won out. Oh, joy! The old Redwood still stands.” Old Stovepipe was renamed the General Eisenhower in 1972.

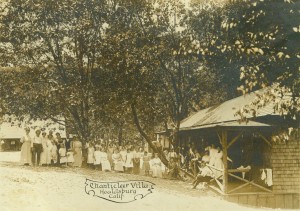

Some fourteen years later, in 1910, a San Francisco Frenchman by the name of Auguste Pradel and his wife Victorine bought 130 acres, from E. Dufore and his wife Hortense on the north side of Fitch Mountain in which the old tree still stands. They established a French resort to cater to San Francisco’s French community. In its day the Villa was the leading French Resort north of San Francisco with accommodations for as many as 200 persons.Pradel built a road, which is today’s Powell Avenue, from Healdsburg to the Villa, and a “wagon” road down to the river below Eagle Rock to what was known as “Frenchman’s Orchard” and later part of the Del Rio Woods subdivision A horse and buggy was sent to the depot on the arrival of each train to take people up the hill. Later a small bus replaced the horse and buggy.

In 1912, August Laurens (Pradel’s son-in-law) took over the facility and made many improvements in the bungalows. He raised money from local businessmen to “put the road leading from the city limits to the Resort in splendid condition.” One wonders just how “splendid” the road was as Felix Lafon remembered that his father’s model T Ford would have to back up on the steepest part of the road to get to the Chantecler. In 1921 this road and the CampRose road on the south side of FitchMountain were made public roads, rebuilt and connected making a six mile loop from Healdsburg’s city limit to city limit.

In 1916 Victor Cadoul and his wife Seraphie purchased the Chantecler Resort (renaming it the Villa Chantecler) for ten dollars in gold coin from the Pradels and expanded the facilities. An article in the June 18th edition of HEALDSBURG TRIBUNE headlined: “THE VILLA ENJOYS BIG RUN” told that there were “nearly 100 guest enjoying the pleasant surrounding and merchants report business in every line with the guest of Chantecler.” (sounded like the merchants got their road investment back). The building had a kitchen and a bar. The dining area was a large screened-in porch on the north side. Cabins were on the east side of the grounds (eventually rooms were built in one of the buildings to accommodate the large number of “single” guests). Overflow guest were put up in tents. It was about this time that the custom of taking guests on a weekly trip to the Italian-Swiss Colony at Asti began.

Ownership changed several times over the years. According to Madeline Delagnes, Cadoul ran the Villa until 1924 when he leased it to her parents Adrian and Marie Cayre. The Cayres kept the Villa until 1926 at which time Codoul once again took over the Villa. Madeline, in an August 29, 1980 HEALDSBURG TRIBUNE article, stated that Pierre Rouquier “built a beautiful home on what is now Borel Road at Samantha Court off upper Powell Avenue. According to Georgette Cadoul Etchell, Victor and Serephie’s daughter who still lives on Scenic Lane, her father built a small home on Borel Road because her mother didn’t want to live at the Chantecler any longer. Victor later sold the home on Borel Road to Pierre Rouquier and built another small home on Scenic Lane off N. Fitch Mountain Road.

When Rouquier took title to the property he expanded the home adding a big room to the home and started the Bellevue Villa which eventually included a full service restaurant, 50 cabins and a bowling alley. Knowing that he now had competition, Cadoul made substantial improvements to the Villa Chanticleer including the famed dining room which was reputed to be the largest room between San Francisco and Eureka. Four years later, due to the lack of water available at the Villa, coupled with the depression that made him land pour, Codoul wanted out and he approached Madeline and her husband Lucien Delagnes who owned the Hotel Gotham in San Francisco.

According to Yvette Delagnes Conz, Madeline and Lucien’s daughter who still lives off Borel Road, in 1934 Cadoul leased the Villa to her parents (they bought the property a year later). The lease covered the 40 acres of buildings and the business, with Cadoul keeping control over the remainder of the 90 acres. Delagnes installed an outdoor “duck pin” bowling alley. On Sunday afternoons $25 in cash prizes were award to the best bowlers and also held the Healdsburg championship. New improvements also included new lighting fixtures. The resort boasted of two milk cows and a “help yourself” cherry orchard. A children’s playground and a playing card grotto under “Old Stovepipe” were also installed. As a predecessor of today, weddings were also held under the big tree.

Three meals per day, a room and wine cost $18 per week. When the Villa was overbooked Madeline would even set up cots inside the old tree. She liked to serve fresh vegetables and guests enjoyed gathering around to help string beans and snap peas. Seven course meals were served with a bottle of wine. During prohibition the wine was served in a cup. Lucien bought 50 gallon barrels of wine from Mel Pedroni for $35 per barrel.

Gil Delagnes, Lucien and Madeline Delagnes’ son who now lives in Windsor, said that when he was a child he would help Frank Vatalli count the money from the 10, penny, nickel and quarter slot machines that were set in and around the Villa. Gil’s pay allowed him to buy the model planes and cars that he loved to make as a child. His parent’s share of the slot machine revenue helped pay for the family’s annual vacations. Partaking in the slots were many local and state politicians who would visit the Villa during the summer months.During the 1940’s the Delagnes’ subdivided the 16.7 acres that currently comprise the Villa and the residential lots that now surround the property. Also in the 1940’s The Delagnes’ let the Pradel’s build a home on a northeast part of the property which they lived in until their death. In gratitude, upon his death Auguste left four thousand dollars for the care of the Villa.

In 1945, they sold the property to two San Francisco men Jack Kent and W. Johnson. This is where legend mixes with reality and fantasy with facts. Madeline claims that Kent mentioned to her that they planned to build a casino for “the Hollywood people.” “One fellow talked a lot of, you know, b.s. He was a liar – pouf! He was not bad looking, though.” She said that they wouldn’t sell until Kent dropped his plan to convert the property to a casino.

On the night of September 14, 1945, while 200 guests were dancing in the famed dining room a fire started in the kitchen. All the guests were safely evacuated but the dining room was burned to the ground. Kent and Johnson rebuilt the beautiful existing main building on a lavish scale and were nearing a reopening date.

Then, on May 11, 1947 a Santa Rosa man named Nick DeJohn (aka Nick Rossi), at one time allegedly involved with Al Capone’s Chicago mafia, was murdered in San Francisco. He had been strangled and was found in the trunk of his car. Soon after, an anonymous source informed authorities that Rossi was connected with a man who was planning a “night spot” at one of the resorts in Healdsburg. All fingers pointed to Jack Kent. Charges were never pressed and Kent vehemently stated, “I’ll give this whole place to anybody who can prove I ever met, saw, nodded, or even spoke to this gangster in my whole life.” But the idea of the Villa as an upscale gamblers’ joint was never fully erased. The six foot by six foot walk-in, impregnable safe that’s still in the Villa’s basement added to the speculation. Soon after DeJohn’s death, and with only the landscaping remaining to be finished, Kent and Johnson declared bankruptcy and all construction ceased. Coincidence?…

As for the Villa’s use as a brothel, The Villa was named Chanticler by Cadoul in the early 1920’s. He took the name from a French fable LeRonain de Renard which was/is a satire on human conventions and morals. Chanticler was a rooster in the fable. The name was derived from “chante claire” which means “clear singing” as in the rooster welcoming the dawn. A 1984 Press-Democrat newspaper article on the Villa claimed that the rooster is a French symbol for a bordello, a fact which is disputed by Yvette. As far as anyone knows this is as close to a brothel as the Villa has ever come.

When it was first built in 1910 by Pradel, the Villa was known as Frenchman’s Resort. In a May 1972 memo from City Administrator Edwin Langhart to the Petaluma sign maker included a sketch of what the Villa’s new sign (the one that now stands at the entrance to the Villa) was to look like. This sketch had only one e in the spelling; however, the new sign was delivered with the double e in the name. Whether the sign maker made an error or if he was instructed to make the change no one knows but the Villa Chantecleer now has the double ee and will so for ever more.

The Villa languished for eight years until SonomaCounty forced a sale for back taxes in 1955. With no bidders, two tradesmen who had filed liens for unpaid work for Kent and Johnson, reluctantly took title for the sum of the unpaid taxes. During this time the City of Healdsburg was in a quandary. They had been planning to use what is now the Longs shopping center on Center Street for a new city hall. After a report from a San Francisco consultant stated that the highest and best use was shopping, the City dropped its plans for a city hall at the site. The town had also outgrown the old American Legion Hall, which was also on the Long’s site, as a community center. When the Villa became available and the same consultant said that the resort would make a splendid community center, the City the 17.04 acre Villa for $45,000. The purchase price included the Villa, annex, 20 cabins (all but four were torn down) and all equipment. The City annexed the property and spent $150,000 finishing the landscaping and made upgrades.The 50 by 70 foot dining room has many large widows with views of Mt.St. Helena and CobbMountain. It is served by a kitchen with four big ranges, ovens and other appliances. On the other side of the lobby is the ballroom, with an oak floor and a large fireplace. Between these two is the Redwood Lounge, a horseshoe-shaped bar with 22 stools, and eight booths along the sides. The painting behind the bar was commissioned to Lloyd Wasmuth of Santa Rosa by Kent & Johnson. It is a technique called “juxtaposition,” in which every brush stroke is a small square. The painter took it home after the bankruptcy but the City bought it back for $250 and reinstalled it. The annex has one large meeting room and a small kitchen. There are picnic and barbeque areas for 200-300 persons, parking for about 200 cars, tot-lot, lots of trees – oak, redwoods, eucalyptus, acacia, madrone – and 10 acres of undeveloped land.

Since its purchase the City has invested, and is still investing, substantial amounts of money to keep the Villa up to date. In the mid 1980’s the Villa was losing about $10k per year as compared to about $50k per year today. Adjusted for inflation, this is relatively the same amount. The City is now working on new programs to generate revenue which will not only close this revenue gap but also generate an income surplus. As Healdsburg’s most treasured social venue and the keeper of Old Stovepipe, “You have battled against all odds and won out. Oh, Joy!” The Villa still stands!

Photos Courtesy of Healdsburg Museum

Read More